Correlations are like two peas in a pod - they just can’t be separated. In machine learning, correlations are like the secret ingredient that makes our models stand out. They help us identify patterns and relationships between features, and guide us in selecting the most relevant variables to predict our target variable. Correlations are the spice that brings flavor to our machine learning recipes, and the glue that binds our models together. So, let’s embrace correlations, and make some deliciously accurate models!

Correlations

1) Pearson Correlation Coefficient:

Continuous variables

This is the most commonly used method for measuring the linear correlation between two variables. It computes the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two continuous variables.

- Python Code:

# Compute Pearson correlation coefficient between two columns

df['column1'].corr(df['column2'])

-

Formula:

$\rho_{X,Y} = \frac{COV(X, Y)}{\sigma_{x}\sigma_{y}} = \frac{\sum_{i=2}^{n}(x_{i} - \bar{x})(y_{i} - \bar{y})}{\sqrt{\sum_{i=2}^{n}(x_{i} - \bar{x})^{2}}\sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^{n}(y_{i} - \bar{y})^{2}}}$ -

Intuition:

It is essentially a normalized measurement of the covariance. -

Assumption/Limitations:

- Relationship between the two variables is linear.

- Variables are normally distributed.

- There are no significant outliers in the data.

- Relationship between the two variables is linear.

2) Spearman Rank Correlation Coefficient:

Continuous and ordinal variables

This is a non-parametric method for measuring the correlation between two variables. It computes the strength and direction of the monotonic relationship between two continuous or ordinal variables.

- Python Code:

# Compute Spearman rank correlation coefficient between two columns

df['column1'].corr(df['column2'], method='spearman')

-

Formula:

$r_{s} = \rho_{R(X), R(Y)} = \frac{COV(R(X), R(Y))}{\sigma_{X}\sigma_{Y}} = 1 - \frac{6\sum_{i=1}^{n}d_{i}}{n(n^{2}-1)}$ where $d_{i} = R(X_{i}) - R(Y_{i})$ -

Intuition:

It is the Pearson Correlation of the ranked variables. -

Assumption/Limitations:

- The relationship between the variables is monotonic.

(i.e. as one variable increases, the other variable either also increases or decreases) - Easier to compute compared to Kendall’s Tau correlation.

- May not be appropriate for small sample sizes.

- The relationship between the variables is monotonic.

3) Kendall’s Tau Correlation Coefficient:

Continuous and ordinal variables

This is another non-parametric method for measuring the correlation between two variables. It computes the strength and direction of the monotonic relationship between two continuous or ordinal variables.

- Python Code:

# Compute Kendall's tau correlation coefficient between two columns

df['column1'].corr(df['column2'], method='kendall')

- Formula:

$r = \frac{(\text{number of concordant pairs}) - \text{(number of discordant pairs)}}{\text{number of pairs}} = 1-\frac{2(\text{number of discordant pairs})}{(n \space \text{choices} \space 2)}$

where “concordant” between two variables being:

$\text{sign}(X_{2} - X_{1}) = \text{sign}(Y_{2} - Y_{1})$

-

Intuition:

The intuition behind the formula is that if there are more concordant pairs than discordant pairs, then the variables have a positive monotonic relationship, and the value of tau is close to +1. -

Assumption/Limitations:

- The relationship between the variables is monotonic.

(i.e. as one variable increases, the other variable either also increases or decreases) - More robust to outliers compared to Spearman’s Correlation.

- Handles tied ranks (i.e. when two or more observations in a dataset have the same value) better than Spearman’s Correlation.

- Requires a larger sample size than Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient to achieve the same level of power.

- The relationship between the variables is monotonic.

4) Point-Biserial Correlation Coefficient:

This is a method for measuring the correlation between a continuous variable and a binary variable. It computes the strength and direction of the correlation between a continuous variable and a binary variable (coded as 0 or 1).

- Python Code:

# Compute point-biserial correlation coefficient between a column and a binary column

df['column1'].corr(df['binary_column'], method='pearson')

- Intuition:

The point biserial correlation coefficient ($r_{pb}$) is a correlation coefficient used when one variable (e.g. $Y$) is dichotomous; $Y$ can either be “naturally” dichotomous, like whether a coin lands heads or tails, or an artificially dichotomized variable. In most situations it is not advisable to dichotomize variables artificially. When a new variable is artificially dichotomized the new dichotomous variable may be conceptualized as having an underlying continuity. If this is the case, a biserial correlation would be the more appropriate calculation. The point-biserial correlation is mathematically equivalent to the Pearson (product moment) correlation; that is, if we have one continuously measured variable $X$ and a dichotomous variable $Y$, $r_{XY} = r_{pb}$. This can be shown by assigning two distinct numerical values to the dichotomous variable.

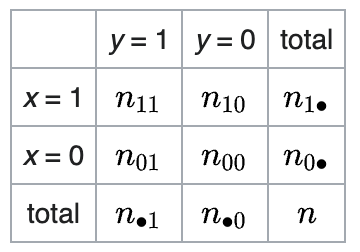

5) Phi Correlation Coefficient:

Binary variables

This is a method for measuring the correlation between two binary variables. It computes the strength and direction of the correlation between two binary variables (coded as 0 or 1). The value range of a phi correlation coefficient is between -1 and 1, inclusive with a phi correlation coefficient of -1 indicates a perfect negative association between the two variables, 0 indicates no association, and 1 indicates a perfect positive association. In other words, a higher absolute value of the phi correlation coefficient indicates a stronger association between the two variables.

# Compute phi correlation coefficient between two binary columns

df['binary_column1'].corr(df['binary_column2'], method='phi')

-

Formula:

$\phi = \frac{n_{11}n_{00} - n_{10}n_{01}}{\sqrt{n_{1 \cdot}n_{0 \cdot}n_{\cdot 0}n_{\cdot 1}}}$ -

Intuition:

The intuition behind the phi correlation coefficient is that it compares the observed frequencies of the two variables to the expected frequencies under the assumption of independence. If the two variables are independent, then the observed and expected frequencies should be similar, and the phi correlation coefficient will be close to 0. On the other hand, if the two variables are associated, then the observed and expected frequencies will differ, and the phi correlation coefficient will be higher. -

Assumption/Limitations:

- The phi correlation coefficient may be affected by the prevalence of one of the categories. When one category is more frequent than the other, the correlation coefficient may be biased towards that category.

- The phi correlation coefficient only measures the strength of the linear relationship between two variables and may not capture other types of relationships, such as non-linear or curvilinear relationships.

- The phi correlation coefficient may be affected by the prevalence of one of the categories. When one category is more frequent than the other, the correlation coefficient may be biased towards that category.